Assessing the economic impact

Assessing the economic impact of the Paris Agreement

Frédéric Babonneau, Alain Bernard, Alain Haurie and Marc Vielle. Meta-Modeling to Assess the Possible Future of Paris Agreement. Environmental Modeling & Assessment, 23 :611-626, 2018.

In 2018 we used the modelling tools we had developed through participation in several European research projects to assess the economic impact of the Paris agreements.

The preferred economic approach to implementing a global climate policy is to define a global price pathway and let each actor determine an efficient policy that consists of equating the marginal cost of mitigation and the global carbon price. This global carbon price can be achieved by defining an effective global tax (which will achieve mitigation targets) or an international emissions trading market ("Cap & Trade" system).

A global carbon tax?

In a perfect world, the simplest solution would be to establish a uniform carbon tax applied by all countries. But this assumes that there are no distortions, fiscal or economic, in individual countries and in world trade. The simple fact that in the initial situation the countries concerned tax fossil energy at different rates and that some even subsidise fossil energy consumption by companies or households, contradicts this assumption. Apart from the above-mentioned distortions, a uniform carbon tax has two other disadvantages. The first is that its implementation can be circumvented in each country through tax policy or other schemes that would reduce or even cancel out the effect of the carbon tax, such as subsidising equipment that produces or uses fossil energy. Furthermore, such a scheme may not work in a decentralised way, because of the difficulty of finding a supranational authority to carry out the necessary checks and balances. The second disadvantage is that a uniform carbon tax has equity effects, within countries although these effects can be corrected by national tax policies, but more importantly between different countries, which can be corrected by transfer payments that are difficult to design.

Or an international emissions trading scheme

A global market in tradable permits does not have these drawbacks. The only initial collective decisions are (i) the setting of a long-term trajectory for global GHG emissions or, more simply, a global budget for cumulative CO2 emissions over the period in question and (ii) the distribution of emission rights to the various countries, which can then trade them on an international market. Once the rights have been allocated to the countries, the market can operate in a completely decentralised manner. It is up to each country to determine its national emissions reduction policy and its position on the international carbon market, i.e. its supply or demand of permits according to the equilibrium price. The operators on the global market can only be countries because they hold the rights that represent their commitments if they do not trade. They are accountable to the global community for these commitments and for the use of their entitlements. However, it is possible for countries to delegate the trading of permits to national companies under certain conditions. It should be understood that in such a system, the equilibrium prices of carbon at the global and national levels have no reason to coincide. In short, one could say that the difference represents the distortions that exist in the given country.

In short, one could say that the difference represents the existing distortions in the given country, which is mainly the level of existing energy taxes. A country with no (distorting) energy tax would get a domestic tax that is somehow equal to the world price, while a country with a distorting initial tax would get a lower domestic tax (and a country that subsidises fossil energy a higher domestic price in order to cancel the effect of the subsidies). Secondly, a country could give a delegation to domestic companies to operate on the world market, provided that the price difference is compensated (if the world price is higher, the company is positively compensated for the difference).

Reference scenario (BAU)

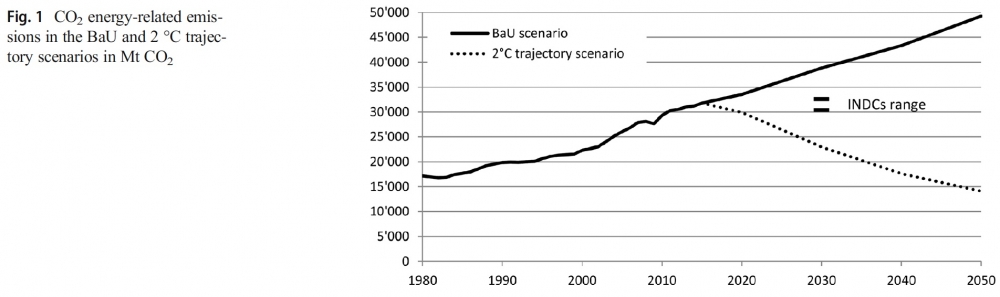

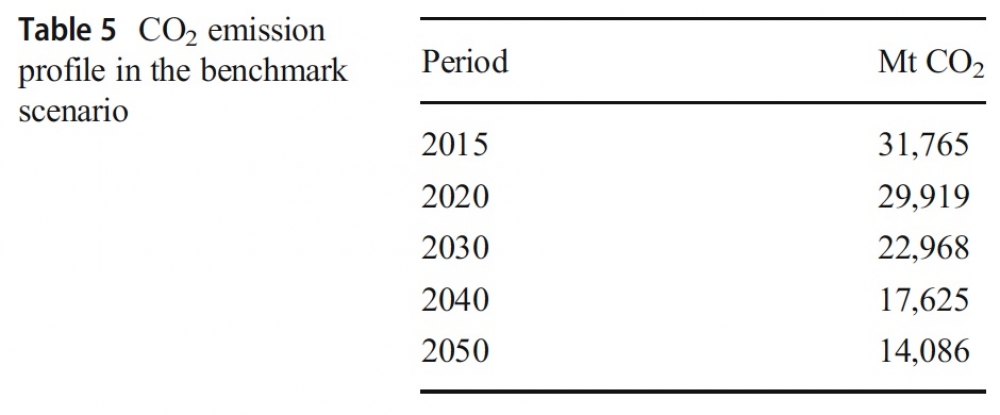

There is now a consensus among climate scientists on a safe cumulative CO2 emissions budget consistent with a 2°C target. In 2013, an IPCC scientific assessment indicated that cumulative carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions largely determine average global surface warming at the end of the 21st century and beyond. The reference emissions trajectory proposed below corresponds to a cumulative budget of 803 Gt CO2 and would leave about 1000 Gt CO2 as a residual budget to be spent after 2050, before reaching a situation of net zero emissions at the global level.

NB: 1Gt = 1 billion tonnes

Sharing the emissions budget

The climate negotiations, which are complex, can be summarized as a matter of sharing the emissions budget between the various countries (160 countries have signed the agreements). These countries are grouped into eight "coalitions", each of which includes countries with converging interests in the negotiations.

We were able to assess the consequences of three types of allocation of emission rights:

An allocation that takes into account the initial situation ("Grandfathering", weighting 70%) and the population (weighting 30%);

An allocation based on Rawls' principles of justice (maxMin criterion); when it is assumed that the eight coalitions will use their emission rights and mitigation policy strategically (Nash equilibrium).

An allocation based on Rawls' principles of justice (maxMin criterion); when it is assumed that the eight coalitions will use their emission rights and mitigation policy in an optimal way (minimization of the global mitigation cost).

The welfare cost is estimated as a % of the discounted sum of consumption that is lost.

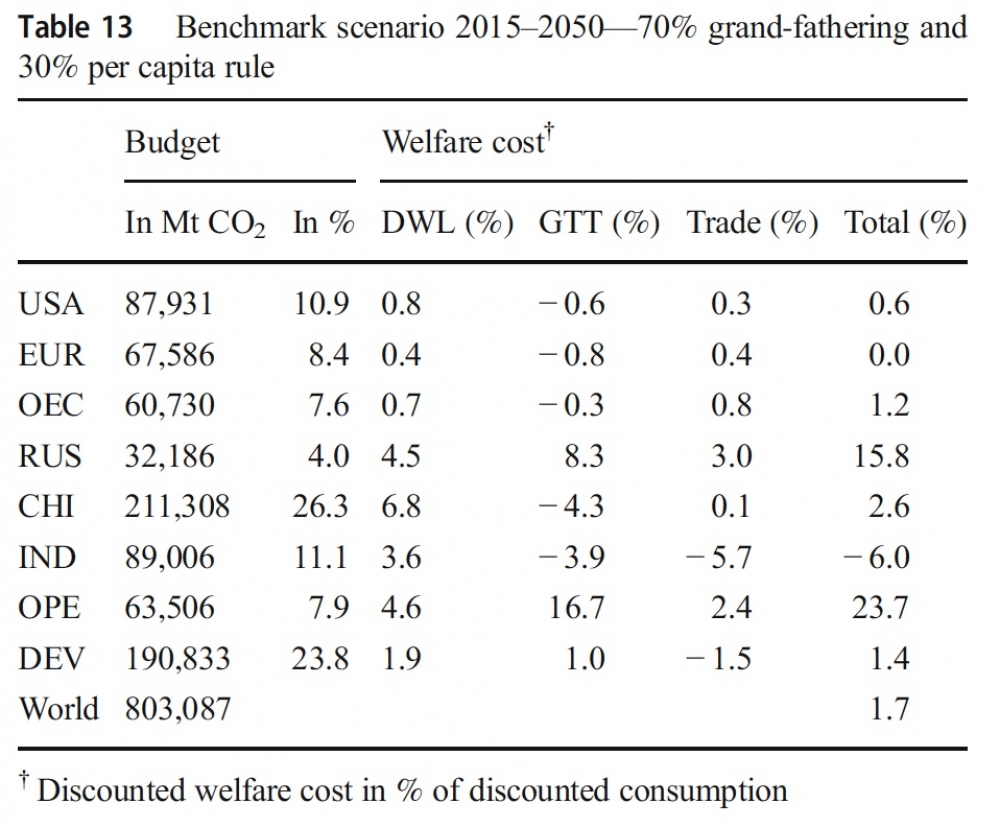

70% Grandfathering-30% per capita

The table below summarises the results of the GEMINI-E3 simulation of macroeconomic balances for the eight coalitions involved.

The first column shows the amounts of the emissions budget allocated to each coalition;

The second column shows the percentage of the budget corresponding to this allocation;

DWL ("Deadweight loss") is the cost of reducing emissions.

GTT ("Gains in the terms of trade") is the (positive) cost or (negative) gain of changing international prices, particularly oil prices.

Trade is the cost (positive) or gain (negative) in emissions trading.

Total is the total cost (in welfare loss) to each coalition for this type of trading outcome.

We see that there are big losers, OPEC and Russia (23.7% and 15.8% respectively), a big winner, India (-6%). Developing countries and China are more penalised than OECD countries. Europe is doing very well.)

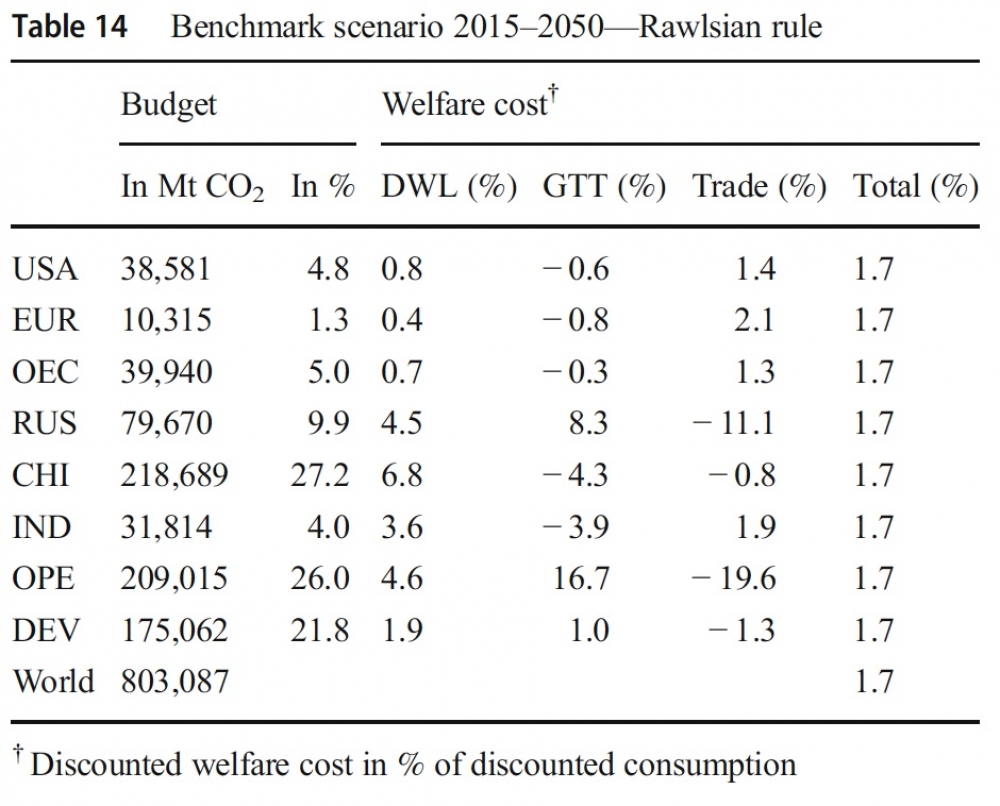

Fair sharing (Rawlsian)

The table below summarizes the results of the GEMINI-E3 simulation of macroeconomic equilibria for the eight coalitions involved when Rawls' justice criterion is applied.

Welfare losses are then equated to 1.7& for all coalitions;

OECD countries receive significantly fewer emissions allowances;

Russia and OPEC are heavily compensated.

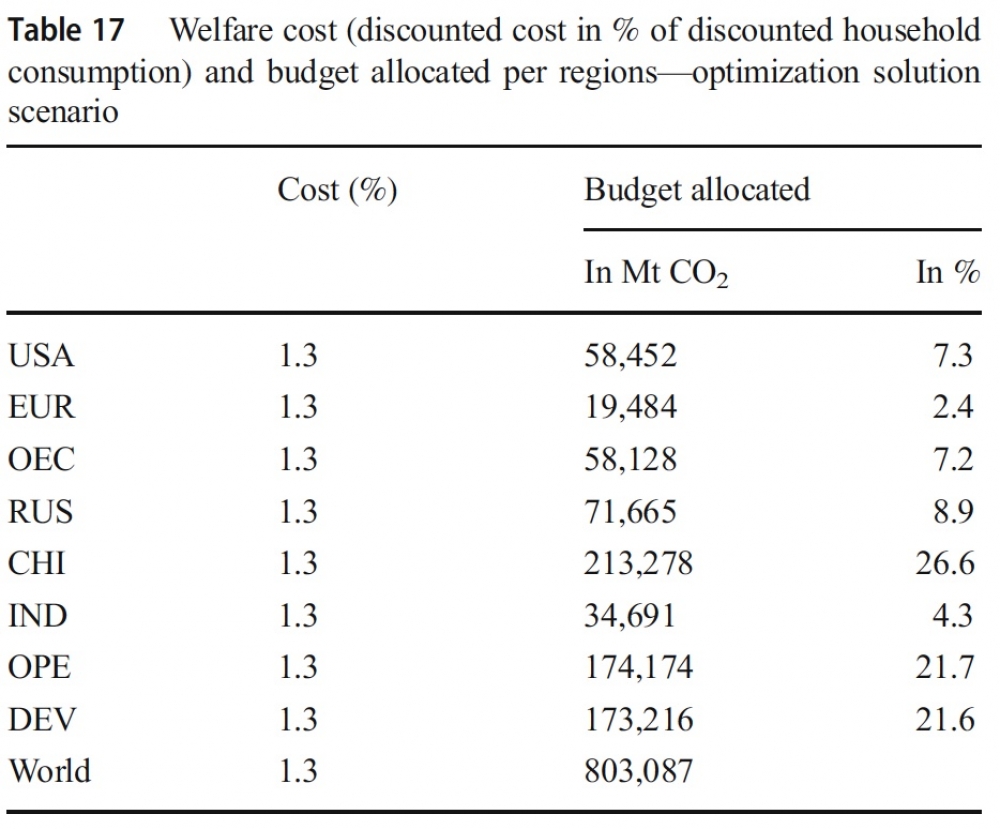

Optimal solution

In a full optimisation approach, each group of countries will be informed of the amount of reduction to be made in each period. The allocation of permits in each period is decided in such a way as to balance the welfare losses in each period, as well as globally over the entire planning horizon.

In this case, the welfare loss is reduced to 1.3%.